What has changed...and what motivates me to continue

10+ years on the White Rose journey...

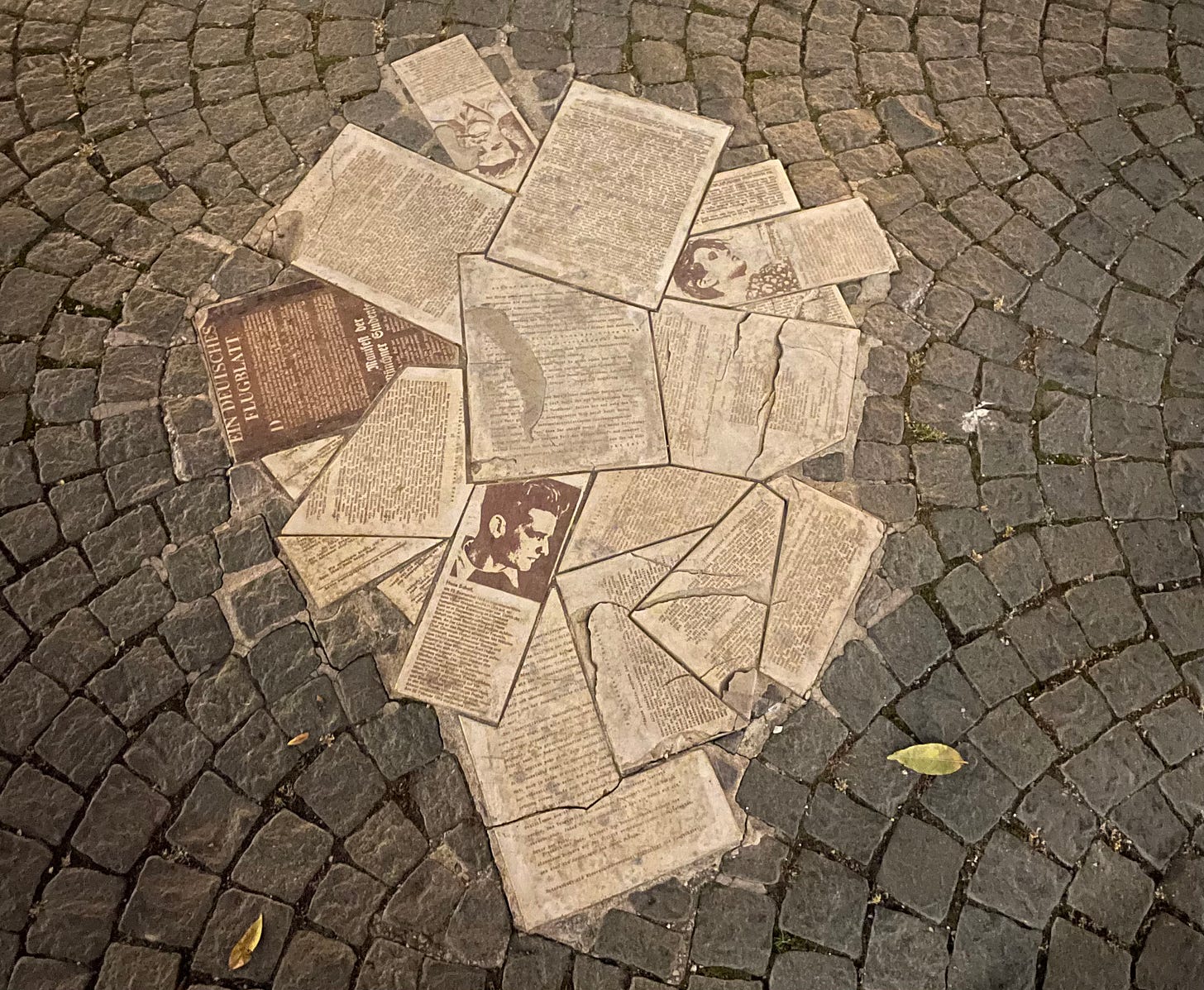

The White Rose.

What would my adult life be without it?

I first learned about Hans and Sophie Scholl in a seminar I took as a freshman in college, called Resistance Writing in Nazi Germany, back in the fall of 2005.

My professor, Elizabeth Bernhardt’s academic expertise is in German language, particularly learning and teaching it as a second language.

But for years, she taught this seminar for freshman and sophomores as a passion project. Her main interest was in Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran pastor who also participated in the German resistance. We also learned about Hans von Dohnanyi, and of course the Scholls.

I remember going to her office one day to discuss a topic for a paper. I became teary-eyed as we talked about these people and what they did. I was so moved by all of it. It was surprising and a little embarrassing, but it was the first indication of a heartstring being pulled, and feeling something in myself resonating with them.

As she said in the first class (I still have my notes), something that makes the resisters of this era unique is that several of them left behind a paper trail. Letters, diaries, and, especially in Bonhoeffer’s case, essays that reveal or give clues about their thinking - and what literature, music, philosophy, and other works influenced them. Whereas the rescuers - just as heroic and worthy of appreciation, if not more so - were entirely focused on doing the work, and not writing about it.

You can listen to my interview with Professor Elizabeth Bernhardt on The White Rose Podcast here:

I wasn’t sure what to do with this information about the German resisters, but from the get go, it brought some healing to my relationship with the arts. I think that’s at least partly why it was so moving to me.

Just the year before, I’d felt a need to distance myself from my obsession with music. My 17-year-old self was convinced that music was too frivolous a pursuit in a world that needs more problem solvers, not more artists/entertainers (unless they are Beethoven-level geniuses)

But now I was contemplating how important the arts were for people who were very serious about doing good in the world.

That train of thought stayed with me throughout my undergraduate experience, ultimately pointing me to Boris Pasternak and his novel Doctor Zhivago, which evoked similar realizations.

Here was a celebrated poet who felt compelled to silence himself for years because of the oppressive treatment of writers in the USSR. For over a decade, he published only translations, despite being declared the most important Soviet poet in the 1930s. Then, in 1957, he allowed the publication of his novel Doctor Zhivago, first in Italy, then in numerous other countries, since publishers in the USSR refused to touch it. The novel quickly garnered global acclaim, in part for being the first book to unmask the cruelty and anti-humanism of the various Russian Revolutions and the Soviet Era in general. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he declined because accepting it would mean permanent exile.

The novel is a love story and, most significantly in my point of view, an auto-biographical artistic treatise, as much as it also contains a social and political critique. Among many things, it is about the nature of art, and nature in general as the blueprint for all creative processes, which in itself was an idea that ran contrary to the revolutionary ideals of his time.

Surrendering to a state of awe of nature and art…these ideas and values point back to 19th century notions of Romanticism, which came into sharp conflict with the new, mechanistic values of 20th century, so much of which glorified man’s ambitions to triumph over nature, whether that be via electricity (Victory Over the Sun), locomotion, advanced military weapons, and, taken to the far extreme by the likes of Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and other despots, playing the role of God when it comes to who shall live and who shall die on a massive scale (and therefore aiming to destroy any religion or spirituality in the process). The world was reduced to its material parts, and in that, there was no place for the unique spirit of the individual.

The members of the White Rose found themselves in similar philosophical conflict, and I don’t think it’s coincidental that they chose a name for themselves that honors the natural world (thereby acknowledging a high power as creator) and its order of things.

These themes and conflicts were fascinating to me and felt resonant and contemporary. I’ve always felt like someone who was stuck in an earlier time period, struggling to make sense of contemporary life and values.

When, years after taking that class, I unexpectedly found Josephine Pasternak’s essay about the White Rose (Boris’ sister), I felt myself encountering some kind of calling or a mission - a strange thing to experience at the age of 22 when I was trying to sort out my own future as I approached college graduation.

I had a sense I’d made some kind of discovery and found a link that few, if any people, knew about or appreciated, between The White Rose, and the Pasternak family - a unique and significantly family given their multi-generational artistic prominence, segments of whom migrated from Russia, to Germany, to England, spurred by the tumultuous first half of the 20th century.

All of this gave Josephine a unique, and for me, a particularly resonant lens for interpreting the events of the White Rose that differed from many a historian.

And then there was the matter of shocking, extreme coincidence:

Josephine had known two members of the White Rose from totally unrelated parts of her life, from when she lived in Germany. To hear of their deaths on the same day via radio in July 1943 when she couldn’t fathom how they knew each other was the ultimate shock for her, and she couldn’t let go of it.

And so, since I found her essay in 2009, it has haunted me and I’ve grappled with what I’m supposed do with the fact that it landed in my lap. My immediate impulse was to write a musical…which I guess reflected my own subconscious desires speaking to me, more than anything else!

Here I am, 16 years later, still grappling.

I have more, much more, to say about the Josephine - Boris - White Rose triangle, and I hope to do that this year. There’s a lot to unpack and while it’s very niche, it is my main “discovery,” something unique that I can contribute to the knowledge-base of this topic, and I have a lot to say about it.

However, I also want to move on at some point! I’d like my various White Rose projects to have their graduations on the horizon, or maybe it’s that I’d like to graduate from this phase of my White Rose work (the musical in particular), since I have so many other projects I want to do.

The metaphor is intentional. This project grew out of my college and grad student years and it has served largely as an educational experience for me to transform from non-artist to someone practicing in a variety of artistic disciplines. It’s been my DIY PhD program. Also, it’s all about university students.

I don’t know whether this “graduation” is 1 year away or 5 years away, but it’s a new intention for me.

What has changed that makes it time to move toward graduation?

Me

As I mentioned, in 2009 I received this spark of inspiration that was completely unexpected and I felt totally unequipped to bring it to life. It wasn’t until 2014 that I even acknowledged it as something I wanted to do, and then until 2017 until I began trying to do it. Since then, I’ve been on a more or less consistent path of developing my artistic and creative skills to do this project

That’s the greatest gift this project has given me - direction.

It pulled me from a path that I was on as a bystander to art making to now, doing so many things I only hoped and dreamed of, things I thought would remain as high school nostalgia, not anything I’d do “for real” as an adult.

The White Rose has been my university, my grad school, my education in a handful of subjects, from historical research, to composition, to piano and singing, to playwriting, artistic collaboration with a wide range of creative professionals, producing in a wide variety of formats (recordings, podcasts, live and virtual workshops, staged production), and more.

I’m certainly not done learning but this was a huge education to get me to the point where I have the skills and confidence to do this project…and to feel excited and confident enough that I can do others.

2. The show

I set out to write a musical about The White Rose…but then it turned into an autobiographical piece, which was hard for me to accept. How dare I put my own story on equal footing with people from the past who have done something truly notable, whereas I have not?

Another question bugged me: what if my life hasn’t played out enough to even know the story I’m telling? I think that was a correct insight…and now I believe the story has sufficiently played out for me to package it up, but it has taken a while to see that.

Part of the challenge was separating out what parts of my true story belong in this iteration of my work and which ones don’t. It has been hard for me to separate out those threads, especially since I have an annoying obsession with what is true and authentic, which I can only let go of when I feel like I have a good reason.

What helped me untangle the threads over the last two years of essentially pausing this project was giving other parts of my story a place to live and be expressed so that The White Rose doesn’t need to carry everything. Writing, recording, and releasing my album Piano Girl helped give a my origin story as an artist a particular place to live. I have another project in an early stage that gives my fascination with Boris Pasternak and Doctor Zhivago a place, so The White Rose doesn’t need to carry those elements either.

And now I’m once again questioning whether The White Rose needs to be autographical, or whether yet another, different framing is where the piece is heading. We’ll see! More experiments, I suppose.

3. The world

It’s shocking how much we’ve collectively gone through since I started on this project. As Josephine wrote in her 1953 essay about The White Rose,

“The world of today is dominated by the notion of speed, from the ever increasing velocity of means of locomotion and communication to the exaggerated rendering of a Chopin study, it is the same precipitate hurry. This incessant urge of ‘over-taking’ is a symptom of moral disease, as if mankind feared to halt for a moment, lest it should find itself confronted with emptiness.”

I remember reading that and thinking, what a striking framing for her commemoration of these people…how much it continues to apply to today, to the many “todays” since I first found her essay.

Our world continues to seek out and need sustenance from stories like the White Rose, for many reasons.

Most personally, after October 7, 2023, being Jewish means something different. It feels different.

Working on a show about Holocaust-related subject matter means something different, and feels different.

Among many other relevant things that have happened in the world since I started this project and in more recent times.

I have a lot of thoughts and feelings about this that maybe I’ll share at some point, but I’ll just leave it at that for now.

I met my “Josephine”, and maybe that was the point in this whole journey

Just weeks before I released my concept album and podcast back in 2022, I visited the website for The Center for White Rose Studies.

I’d been on their website a zillion times before, but this time it was different.

It was a new website, and there was an online store with incredible materials for purchase, specifically translations of the gestapo interrogation transcripts of many members of the White Rose.

Immediately, I ordered a bunch of things. It was a treasure trove of just the kind of primary sources I’d been hoping to find for years!

And…I was aware it might challenge everything about what I understood the White Rose to be, which is what has happened.

Since then, I’ve developed a relationship with Denise Heap, the force of nature behind this incredible body of research and original work that pursues the truth of what the White Rose (and other instances of German resistance) was about, not just restating the legend of what most writers on the topic have shaped it to be. Those things are starkly different.

Over the last few years, I’ve visited Denise at her home twice, she came out to Los Angeles to see my show in 2023, and she even invited me to Germany to attend and have my music presented at the Willi Graf memorial (which I wrote about here).

Denise began this work in the 1990s, embarking on what she thought would be a 6-month project. Now, over 30 years later, she’s still at it.

Her work on the White Rose is important. It’s fueled by her commitment to finding the truth, and a mission to honor the legacies of all those involved, especially the many individuals whose contributions were minimized or written out of the story.

Learning from Denise over the last few years has been one revelation after another. It has made my work on my musical immensely more complicated, in the best way.

I wanted to know the truth, and then, what do I do with that information, even if it unravels the neatness of the show I was previously writing? That’s my continued creative conundrum, but a challenge that I’ve earned from my own persistence.

It’s unfortunate, but there is a dearth of rigorous academic scholarship on the White Rose, for reasons that are fascinating and frustrating. Denise’s work has become the gold standard because of its quality, detail, and focus on historical accuracy. In fact many individuals in the US and Germany have relied on her transcriptions and on her White Rose Histories volume 1 and 2 in order to get their PhD degrees!

Unfortunately, her discoveries and work product have frequently gone uncited, uncredited, or plagiarized, perhaps because she has done these decades of work without a doctoral degree or an institutional affiliation. She’s done it all alongside another career, significant family obligations, and more. To me, that is inspiring, deeply impressive, and speaks to the pure motivations that drive her. This also gives her the freedom to stay true to her values and interests, rather than needing to “publish or perish” at any cost or chase grant money that comes with an agenda.

So what began, and still is, as a mission to honor the work and legacy of Josephine Pasternak by revealing her interpretation of the White Rose, has evolved into a desire to honor and elevate Denise’s work.

Josephine pointed me in this direction, following those threads and that impulse led me to Denise, whose work is truly worthy of greater recognition and amplification.

I’m still exploring exactly how or all the ways I will do that, but it’s a motivator behind my various forthcoming White Rose-related projects.

Follow Denise’s work!

In the meantime, if the story of German resistance during WWII and/or the White Rose speaks to you, I hope you’ll check out Denise’s fantastic Substack, Why This Matters. You’ll learn so much, as I continue to do! I’ll be sharing some of her posts here on occasion as well.

So with all that…I hope to continue to ride the waves of momentum to continue my contributions to this subject matter, and join Denise and Josephine in honoring the legacies of those who contributed to the White Rose.

Jennifer, thank you so much for this post. It came at a good time when I needed a bit of encouragement.

White Rose scholarship has been damaged first by our own Marshall-McCloy funding that was willing to overlook Nazi backgrounds if people would take our money and teach democracy. Inge Scholl and Jürgen Wittenstein both excelled at that grift. We paid both of them to reinvent themselves.

Next, what had been the Deutsche Akademie (founded in 1925) was simply rebranded as Goethe Institut after the war. Its first five directors had all been high-ranking Nazis. That means that the Goethe Institut was headed by people who never recanted their Nazi ideology until 1972! That means when I was in high school, the films and newsletters we received from GI had all been published by unrepentant Nazis. Same situation for Institut für Zeitgschichte, the contemporary history organization based in Munich.

It was almost a quid pro quo with Inge Scholl and Wittenstein. They kept one another's secrets. Did you know that the GI distributes Inge's legend-ary WR book free of charge to US schools and universities? Sigh.

It feels like an uphill battle, not one that many people are willing to join. I am very grateful for you, for your voice, for your Presence in righting the historical record.