In the first draft of my musical, The White Rose, I cut out one of the key figures from the story - Willi Graf.

Below I share the long story of why I removed him in the first place, why I ultimately brought him back, and how that affected me (it did, in a big way).

There were over 100 people involved with the White Rose resistance movement in Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1943. But the six individuals who were executed by the Nazis in 1943 are considered the core group:

university undergraduates Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Christoph Probst, Willi Graf, and their professor, Kurt Huber.

When I wrote the first draft of my musical in 2019, I’d already put in a few years of research. But the trouble with researching the White Rose, especially as someone who doesn’t speak German, is that nearly every book published swings closer to historical fiction than a well-cited factual account.

Note: I wasn’t aware of the Center for White Rose Studies’ excellent publications until the end of 2021. These are definitive, meticulously researched resources and careful translations that I wish I’d had access to earlier!

From the beginning of my research, I was drawn to the written words (even in translation) of these people, first and foremost. I was already familiar with the letters and diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl, available in English translation, and I relied on these documents to understand and write these characters.

Later I learned (from Denise Heap, founder of the Center for White Rose Studies), that these letters were heavily censored by Hans and Sophie’s older sister Inge, redacting the less flattering bits, possibly relating to Hans’ homosexuality, Sophie’s suicidal tendencies, or the Scholl family’s unsavory comments about Jews (not to mention, their Nazi entanglements). For instance, why are there no writings relating to Kristallnacht when there are many letters surrounding that date?

Dealing with the many shocking discoveries about the Scholls (the ones noted above are just the tip of the iceberg) has presented one of the greatest challenges to my telling of this story. But that’s a topic for another day.

Still, I value the Hans and Sophie letters and diaries and how their characters are revealed through these documents - especially since that’s what enabled me to feel like I could speak for them through words and music.

Even before that though, my initiation into this project came through the words of Josephine Pasternak. Josephine was the sister of the famous Russian poet and novelist Boris Pasternak. Coincidentally, she knew two of the men involved in the White Rose, Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber. Josephine wrote an essay in 1953 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the deaths of these people - an essay that was never published (you can read it on my website here).

When I found the document in the Hoover Archives at Stanford in 2009 (along with a handful of rejection letters from journals declining to publish it), I felt that fate had handed me a mission to fulfill - to somehow make her words heard.

Josephine was perhaps the first person to write about the White Rose in the English language - she was living in Oxford, UK in 1943, having fled first from Russia, then Germany, when she learned via a BBC broadcast that the Nazis had murdered these two men she’d known from an earlier time in her life.

Knowing what I knew about her and her family during the tumultuous first half of the 20th century, it was clear to me that she understood things about the White Rose that would not be obvious to an American reader today.

Josephine’s words anchored me into her perspective on the White Rose, which emphasized factors that many other writers on the subject might overlook. Things like this:

Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were closest to her heart, understandably, since she knew them. In her essay, she included quotes from their last letters to their families before they were executed, which gave me a glimpse into their essence manner of communicating - enough for a starting point.

For my first draft, I had not seen any words written by Christoph Probst, but his circumstances felt distinct enough from the others - of the five students, he was the only one who was married with young children. Also, his stepmother was Jewish (the other members had no Jewish relatives). Those facts put his actions and sacrifices into a different context from the others, and gave me something to grab onto.

And then there was Willi Graf. I felt like I knew nothing about him, beyond basic biographical facts, which were weren’t enough to clue me into his character. The only element that resonated as something usable was the fact that he was held by the Nazis for longer than all the rest.

Whereas Sophie, Hans, and Christoph were murdered in February 1943, and Alexander and Professor Huber in July, Willi, although arrested around the same time as the others, faced his death in October of that year.

He was held in solitary confinement and interrogated regularly, in the chance that he’d reveal more names. He never did.

What must it have been like to remain in prison for those months, knowing that his friends had died and someday it would be his turn?

There was definitely something interesting about all of that, but it didn’t feel like enough to work into the story. Besides, I figured I’d compress the timeline of their deaths for dramatic purposes.

Basically, I couldn’t figure out what he would have to say about things and how. So I cut him out.

Not the only one to do it

Perhaps it’s not a totally egregious thing to do in making a dramatic work. Sure, there’s a standard of accuracy that one would hope for (though not necessarily find) in a news article, a documentary, or an academic history book.

But for a novel? Or a movie? Or a musical, of all things? Dramatic license is expected, even encouraged. The creator’s perspective is revealed at least in part through their approach to adaptation, especially in more creative adaptations.

From character conflation to manipulating timelines, to a wide variety of other changes, a creator can still convey the essence even if the truth gets blurred, and there’s nothing wrong with that. In fact, that can be precisely what we appreciate most about the piece.

Over the years, I’ve received many surprising, specific suggestions of ways I should alter the story for dramatic purposes.

And I’m not the only one to cut a key member of the White Rose out of a White Rose musical.

White Rose: The Musical (which ran for a few months off-Broadway earlier this year) eliminated Alexander Schmorell from the story.

I have not seen this show - in fact, I know very little about it, a deliberate choice in order to protect my own process. But I can understand the impulse and the reason to sacrifice historical accuracy for an artistic objective.

Being honest though, I cut Willi Graf not for good dramatic reasons, but out of laziness. I hadn’t done the work to figure him out.

When I confessed all this to my mentors, Susan Blackwell and Laura Camien of The Spark File, in the summer of 2020, their reaction was, “yeah…you might want to add him back in.” And of course they were right.

Where to begin?

Bringing Willi back

For the purpose of my 2022 concept album, I did the easy task of allocating a few lines in songs to him. I’d given up on trying to write a script that year so that took some pressure off me.

Even then, as I wrote “We Stand Alone” and especially the reprise of that song, I had a feeling that Willi would become more of the story. The opportunity to go from “we stand alone” to “I stand alone” was just too appealing to pass up.

Soon after, I discovered that there are published letters and diaries from Willi, Christoph, and Alexander - in German. I ordered everything I could find, without a plan for what to do with those books.

Later in 2022, I began working with Elizabeth Stern as a translator/collaborator. She’s an American who is fluent in German, a musician with a strong humanities and education background. I didn’t want someone to translate every word, but to read everything with an eye for what I was looking for and then do selective translations from there. It seemed like an awfully nebulous job description but Elizabeth got it immediately and we found our groove easily, beginning with Willi’s letters.

Through Elizabeth, I got to know Willi. His loneliness. His difficulty in connecting with others. Unlike Hans and Sophie, he’d been staunchly anti-Nazi from his teenage years, which isolated him from most of his peers from a young age. Before attending the University of Munich as an undergraduate in medicine, he served in the army on the Eastern front and was traumatized by what he witnessed, such as the German army burning down Russian villages.

How he was an obsessive reader. He loved Shakespeare, and, after his second tour of duty in Russia, Dostoevsky. He played the viola and sang in the Bach choir. A friend of his believed that, had he lived, he might have become a choral conductor. He even wrote music while in prison.

He took his duty as an older brother to his sister Anneliese seriously. She was one of the few people he would confide in, but he also took seriously his duty to mentor and protect her. This served as an interesting contrast to Hans and Sophie’s relationship, of, which very little is revealed through their letters. I sensed an element of competition between them from certain comments made by Sophie, but their letters don’t reveal much.

I was particularly struck by the very last letter Willi wrote to his parents and sisters from prison. I’d actually found an except of it online years earlier, and again, while I did not know how to infer his character arc from it at the time, I was struck by its usually direct communication of love and intimacy:

My dearest parents, my dear Mathilde, and Anneliese,

On this day I'm leaving this life and entering eternity. What hurts me most of all is that I am causing such pain to those of you who go on living. But strength and comfort you'll find with God and that is what I am praying for till the last moment. I know that it will be harder for you than for me.

I ask you, Father and Mother, from the bottom of my heart, to forgive me for the anguish and the disappointment I've brought you. I have often regretted what I've done to you, especially here in prison. Forgive me and always pray for me! Hold on to the good memories.... Stay strong and trust in God’s hand, which shifts things always for the best, even if in the moment it causes bitter pain.

I could never say to you while alive how much I loved you, but now in the last hours I want to tell you, unfortunately only on this dry paper, that I love all of you deeply and that I have respected you. For everything that you gave me and everything you made possible for me with your care and love. Hold each other and stand together with love and trust.... God's blessing on us, in Him we are and we live.... I am, with love always,

Willi

10/12/1943

Elizabeth also found another letter from Willi’s last day, to Anneliese, and that letter gave me goosebumps (I’ve excerpted a few key sections):

Anneliese! I received your letter on the last day and your words brought me great comfort. Now you alone must help our parents in this grief and try to stand in for what I couldn’t be for them. You know how much you have meant to me and I say to you in this last hour how much I loved you. The conversations we had over the last few weeks should help you and be the content for your future life. I will be with you even if I can’t stand by your side in your daily life.

…

You know that I did not act recklessly, but that I acted from the bottom of my heart and with awareness of the seriousness of the situation. And you must see to it that these thoughts and intentions stay alive with our family, relatives, and friends in a very present (conscious and real) way.

For us, death is not the end of life, but the beginning of a truthful life and I die trusting in God’s will and care. There is so much I still want to say to you, but it is so hard in these last moments to speak of them.

…

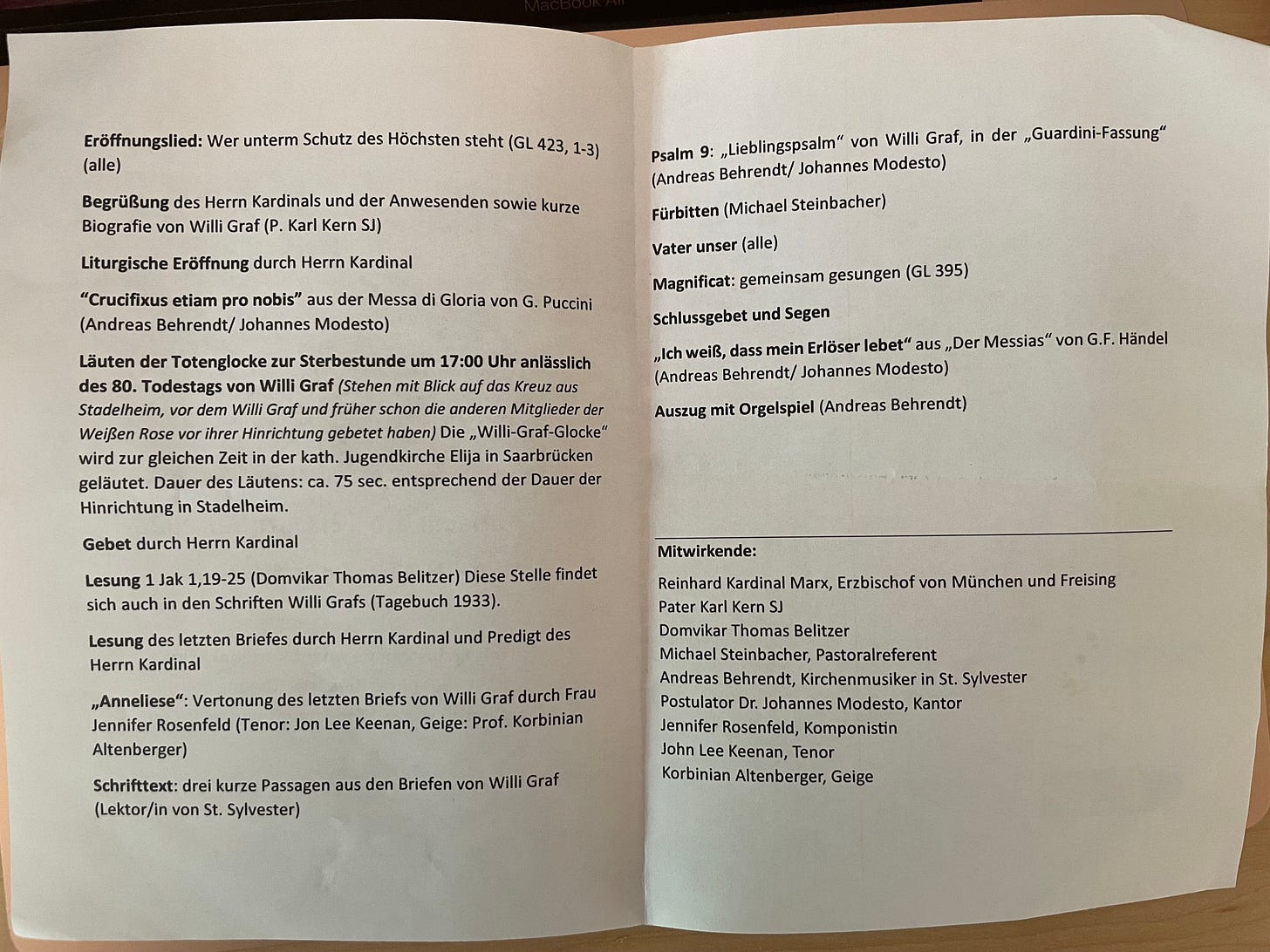

When you listen to the Aria from Handel’s Messiah “I know that my Savior lives”, think of that time we shared in the Odeon. The faith alone is robust and strong for me. Don’t forget me and pray that God will be a gracious judge for me.

Also with my friends you should keep my memory, thoughts, and will alive. You can understand that I wasn’t able to leave my friends a sign. When the time is right, you should connect with them. Especially with Hein Jacobs and Fritz Leist. Also relay to all of my other friends my last greetings. They should carry on what we started. All my books and writing in Munich, Saarbrucken, and Bonn I leave to you. You should do with them what you think is right.

…

So at the end, after trying to keep Anneliese away from any resistance activities, he asks her to carry on his legacy. Which she did, including ensuring that his letters were published.

As I began planning my November 2022 reading of The White Rose, I decided to set these two letters to music.

The concept that seemed so obvious to me was to do a baroque-inspired aria with recitative, accompanied just by solo violin. I wanted something sparse and melancholy to represent Willi’s solitary, final reflections. And I was inspired by Willi’s musical tastes and his reference to “I know that my Redeemer Liveth” from Handel’s Messiah (which I quote explicitly in the piece), and also by Jon Lee Keenan’s voice, whom I’d previously engaged for the role of Willi for the album.

This piece is definitely not something you’d find in your typical musical, but it felt special to me.

I especially enjoyed how, in the production last summer, our director Diana Wyenn had the idea to have our fabulous violinist, Chrystal Smothers, join Jon on stage - and play this 9ish minute piece from memory. It was one of my favorite moments in the show.

Jon Lee Keenan and Chrystal Smothers in the 2023 production of The White Rose. Photography by Mae Koo.

Since I had not yet written this piece when I recorded the concept album in 2021, I had a recording made a few weeks after the production, with Jon and violinist Nathan Cole.

An unexpected invitation

Putting Willi into the show - and specifically putting this unconventional piece into the show - opened up surprising opportunities for me, and brought me closer into the White Rose world.

I invited Denise Heap, of the Center for White Rose Studies, to attend my production in LA last summer. We’d been corresponding since early last year and I even went to visit her at her home about a year ago. She is one of the leading authorities on the White Rose, having researched it extensively over the last 30 years. Her research and resources have been relied upon by scholars around the world, though appropriate credit has often not been given.

I was nervous her seeing my show. What would she think? Would she feel I had respected her knowledge, and all the time she’d spent educating me?

I was relieved when Denise praised my efforts to convey the “true” story, and she was especially taken by Willi’s Last Letters. She said Anneliese, whom Denise had known, would have been proud. And she felt that Jon had captured Willi’s essence perfectly.

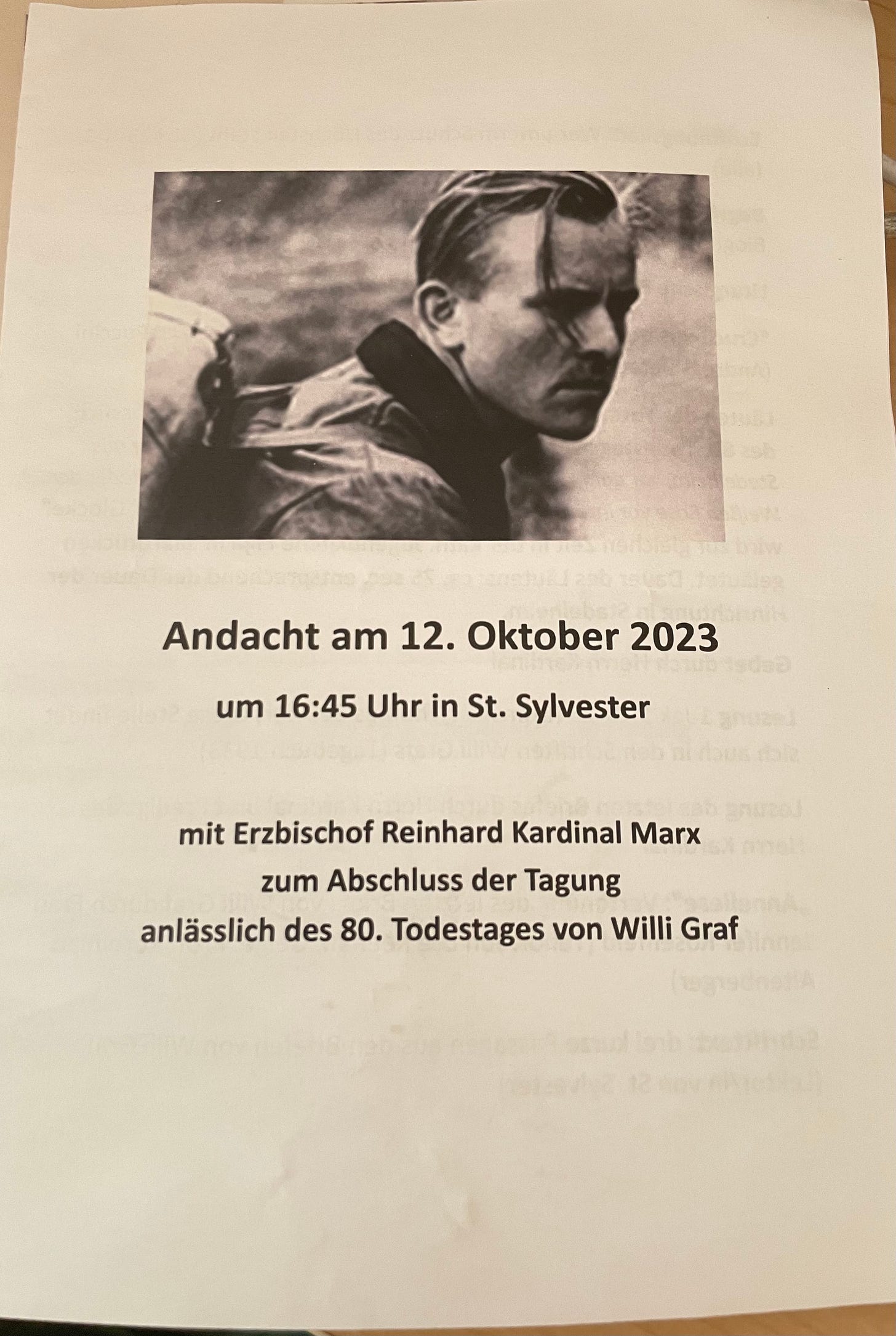

At the opening night reception, she asked if Jon and I would come to Munich to present Willi’s Last Letters at the 80th anniversary of Willi’s death on Oct 12, 2023. It was the first memorial service specifically to commemorate Willi’s life, taking place at the same catholic church in Munich where he was a parishioner. Denise was speaking at a Willi Graf conference associated with the memorial and knew the organizers.

This was the first time anyone had ever invited me to present my music somewhere…and what a context! Here I am, a random American with an interest in the White Rose…and my composition, with English lyrics, would be performed at the very official Willi Graf memorial in Munich? What??

I was on the fence for the various logistical reasons but Jon insisted we should make it happen.

I needed to find a violinist in Germany, so I posted on Facebook - “I need a violinist in Munich on October 12, 2023.” Within a day, I received a message from Korbinian Altenberger, a fantastic violinist in Munich. He was aware of my work with the White Rose, which was of personal interest to him since his grandmother was Christoph Probst’s cousin. It felt like it was meant to be.

Then it was October 7th, and the world changed for Jews everywhere. Even as the news was fresh and still emerging, videos, images, and stories of holocaust-level horrors were flooding in from Israel. I’ve spent time there, I have friends there, and distant family. It’s a place that means something to me.

Being on the other side of the world was of little comfort. As much as any media outlets, or commentators, or social media influencers would like to make it seem that this was fallout from a decades-long political struggle, many of us could only interpret the events (and the often celebratory global reaction to them) as yet another instance of blood-thirsty hatred of Jews no longer simmering or unseen and ignored, but rising undeniably to the surface in our generation, just as it did in the generation of my grandparents, and so many before.

And there was the big question that couldn’t be answered in a matter of hours - what am I doing with my life? Have I made the right choices? My family history, defined by the fact that we are Jews, is one of the most closely held parts of my identity, the nearest to the core of my being, even if it’s something I rarely talk about with others. How do I relate to this part of myself now, held up next to my priorities over the last several years?

I couldn’t imaging flying to Munich of all places the next day. Denise and I were planning to visit Dachau, the concentration camp. The last thing I wanted to do was get on that plane.

Distraction can be a good thing. After a night of doomscrolling and jet lag, I joined Denise the next day at the lovely Seehaus Restaurant on the water in the English Gardens. She said it was a favorite spot for the White Rose students.

She shared about the latest discoveries she’s made, putting together new pieces of the White Rose puzzle. I was yet again in awe of her energy to continue, to keep striving to get to the bottom of the story.

In that moment, a new idea struck me - I should make a documentary about Denise and her discoveries. She was like Josephine to me, but here, real, and of my lifetime. If this journey led me to her, that was also for a reason. Was I willing to follow through on where it was leading me?

We finished our tasty lunch and headed to Dachau.

The Willi Graf conference began the next day. I attended a decent portion, despite the fact that all the presentations were in German, including Denise’s.

Then, on the 12th it was time for the memorial service at St. Sylvester’s Church, where Willi had been a parishioner. I didn’t realize that my composition was basically the centerpiece of the service. Before my piece, the Cardinal read Willi’s letters which featured in and inspired my piece. It was the anniversary of his death, but also the anniversary of the day he wrote those letters.

It’s hard to find words for how witnessing the performance of my piece in this particular context impacted me, because it was one of the rare, deeply spiritual experiences I’ve had in my life (I’m fortunate to have had a few).

There was a unity of purpose in the gathering, probably the largest gathering of people alive to whom Willi Graf, his life, and his sacrifices meant something real and personal. There was no applause after the performance - it was in the middle of a church service afterall, but I felt like it was understood by and meant something to this audience, in a way that would never happen in any other situation.

So many of us desire to impact the world positively in a big way - you could say that’s exactly what Willi gave his life for. In that moment, I felt like I’d honored Willi and that it meant something to people, and hopefully to him, even if in a very small way, even if just for that moment. And, most significant for me, I’d done it through my artistic contribution. I suppose that’s what I’ve been going for all along with this project.

I was left with an overwhelming gratitude for all of it, as well as a recognition of how far I’d made the effort to go in following these threads - for the White Rose overall, and for Willi in particular. I always wanted to be the sort of person who would follow through with things that felt important, even when they were confusing or difficult, and in this instance I felt like I had.

Among people in attendance were members of the Graf family, relatives of other White Rose families, and more. After the memorial, I met and had a long walk with the daughter of Regine Renner, one of Willi’s friends from the Bach Chorale. Then, with Denise, Jon, and Michael Kaufman of the White Rose Institute, who had organized the event, we walked to the University of Munich to see the White Rose memorial and the site of Hans and Sophie’s arrest on February 18th, 1943.

I’ve been fortunate to work with world-class performers in every iteration of this project - which astounds me still. There’s nothing more thrilling than hearing great performers bring my music to life. But again, this context was something unusual and special, and I could tell through their performances that Jon and Korbi felt it too.

Magic in the unexpected

The number of unexpected twists and turns my life has taken as a result of the White Rose is too many to count, and this is one of the big ones.

I love that the person that I had so little to say about that I cut him from the show, became the one who was the reason for me to go and experience the site of the White Rose in Germany for the first time, and not just as a tourist, but as an active contributor to his memorial.

Each of the members of the White Rose had their flaws and limitations, contrary to the heroic story that is often told. Willi was not an exception.

But his courage, commitment to his principles, and his loyalty to his friends, were tested perhaps more and longer than anyone else in the group - and he was steadfast throughout. He experienced so much loneliness and isolation during his short life, and that was also how his life ended - in solitary confinement, facing himself alone in his final months. And his last word on that? It’s in those letters he wrote to his family.

I’m still sorting out my next steps with my musical…it’s still not totally clear to me. But what is clear is that I want to make this documentary with Denise. We start filming this spring. And I wouldn’t be doing that if Willi’s memorial hadn’t brought me to Germany last fall.

Posting this response as Denise, not as Center for White Rose Studies. I too am glad you reconsidered Willi. The person you were going to cut became the person whose life and essence you captured best.

Jo Horne is currently writing a historical fiction YA novel where a person - in 1960s USA - relates what Willi’s friendship meant to him. She’s trying to get Willi as correct as possible. I pointed her to Jon’s rendition of the letters.

Soon!

PS: Ironic that after 10/7, you were in the one country on the planet that unwaveringly supported Israel.